This is a pre-print version of this article. The final, edited version will appear in the online edition of American Literary History 27.3 (August 2015). We will add a link to the final version when it is published. This methods piece works in conjunction with a literary-historical article.

I. The Viral Texts Project and Research Corpus

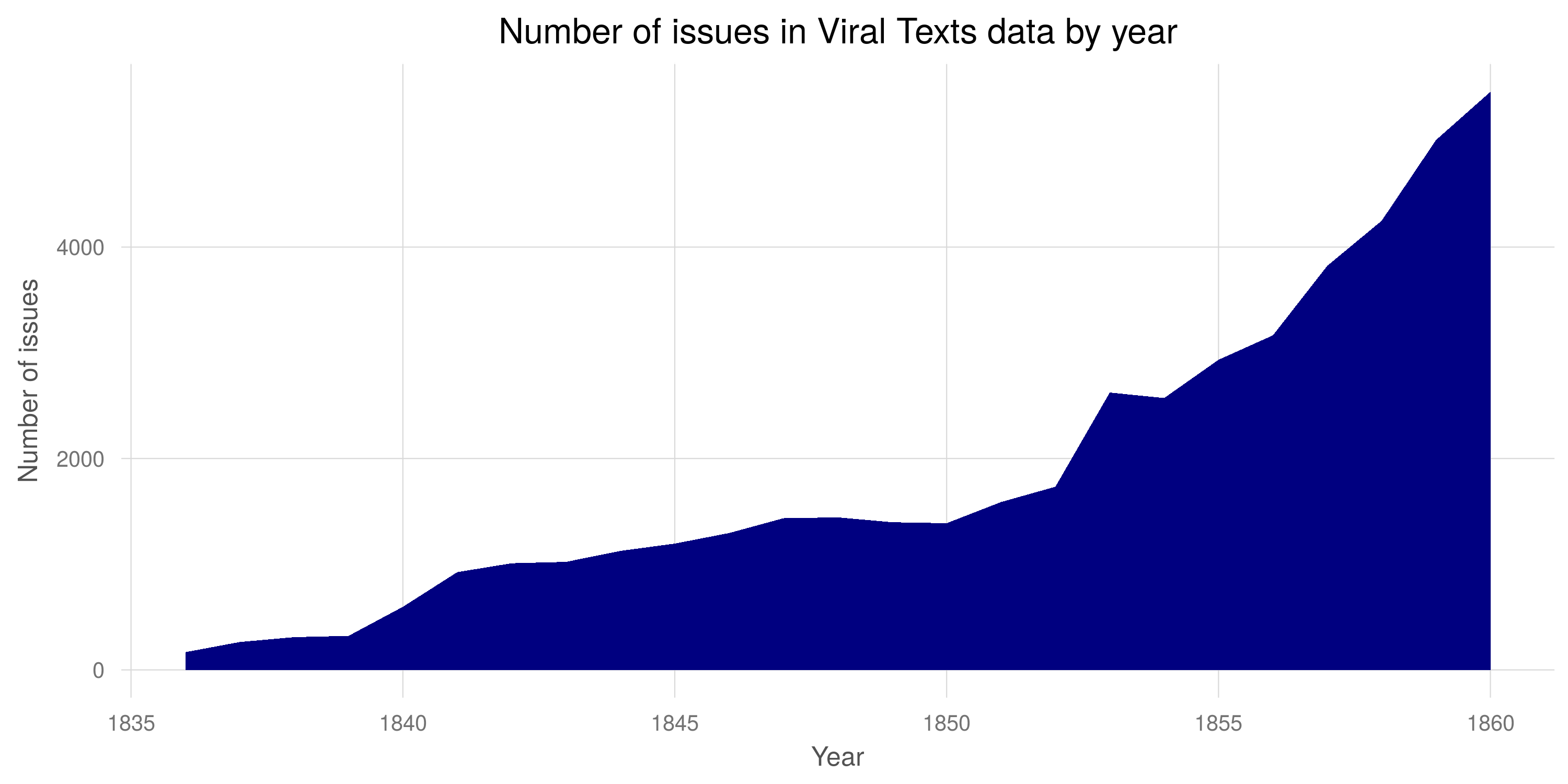

The Viral Texts Project is an interdisciplinary and collaborative effort among the authors listed here, with contributions from project alumni Elizabeth Maddock Dillon, Kevin Smith, and Peter Roby. In the first iteration of the project, we focused on pre-Civil War newspapers in the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America online newspaper archive, in large part because its text data is openly available for computational use. The pre-1861 holdings comprise 1.6 billion words from 41,829 issues of 132 newspapers. Many of the 132 newspapers included in this study are, in fact, iterations of continuously-published entities that changed names or other qualities during their runs; we describe the way we grouped these publications into newspaper “families” in Section IV below. We chose 1861 as our cut-off date not as a periodizing statement, but instead simply to demarcate a limited set of newspapers for our initial tests. The later in the nineteenth century one looks, the richer the Chronicling America archive; while our corpus includes some issues from the 1830s, then, the bulk of it comes from the 1840s and ’50s.

Figure 1. This graph shows the number of issues of Chronicling America newspapers in our data by year, plus the number of issues in Cornell University’s Making of America from 1836 to 1860. You can see the large spike in the number of issues in the final ten years of our analysis.[1]

While the Chronicling America database is large, there are significant gaps in its holdings and problems with its data that influence our results. Chronicling America is not a single digitization project, but instead aggregates historical newspapers digitized through grant-funded, state-level projects.[2] As such, there are statewide gaps in the archive where particular states have yet to participate. Currently, for instance, Chronicling America includes no newspapers from Massachusetts, the research team’s home state and, of course, a major center of nineteenth-century print culture. Even those states that contributed were unable to scan most of their historical newspapers. The bulk of historical newspapers remain undigitized, if not entirely lost. In addition, the raw text data that underlies the Chronicling America collection is, at best, messy. The text was automatically transcribed by Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software as newspaper pages were scanned. OCR makes frequent mistakes, particularly when trying to recognize text on worn or damaged historical pages or across the closely printed columns of nineteenth-century newspapers. In a pilot study matching known texts of 35 poems and stories against the Chronicling America database, we measured an average character error rate of between 5% and 15%, which leads to an average word error rate over 25%. The sheer scale of these digitization projects makes hand correction impossible.

Given these limitations, our analysis necessarily misses far more reprinted pieces than it identifies. When we follow a link from any of our clusters and open a given newspaper page in Chronicling America, we typically see other reprinted texts (often indicated by the conventional “from the…” formula at the beginning or end of the text) on the very same page as the reprinted text we automatically discovered. Often these texts claim to be reprinted from newspapers that are not part of our current corpus, which explains why we have missed them. Other overlooked reprints are perhaps due to exceptionally poor OCR. Finally, we are aware of limitations to our discovery algorithm. Because of editorial changes from the nineteenth century and poor OCR from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the algorithm requires a text to be relatively long to be identified: a text must include enough 5-grams that can overlap with other texts and be recognized as a pattern, rather than just noise. While this method has produced impressive and reliable results from extremely messy data, we know that we are missing shorter reprinted texts, such as many lyric poems, that simply do not contain enough 5-grams to be matched under the current algorithm.

II. Detecting Clusters of Reprinted Texts

In this section, we describe our current methods for detecting pairs of newspaper issues with significant textual overlap, for aligning these issue pairs, and for clustering these pairwise alignments into larger families of reprints. We have previously discussed and evaluated detecting pairs of issues with overlapping content in Smith et al. (2013, 2014) and described our approach to alignment in Wilkerson et al. (2015). Here we will detail the precise methods which contributed to the conclusions Cordell makes in the accompanying ALH paper, “Reprinting, Circulation, and the Network Author in Antebellum Newspapers,” and attempt to translate the computer science scholarship from which we have drawn and to which we are contributing for humanities readers. As Cordell notes in his piece, many of the texts most widely reprinted during the antebellum period are not widely known to scholars today. We cannot, therefore, compile an exhaustive list of “query” texts and find other versions of them in a collection, as one might when trying to detect plagiarism in a given set of students’ essays. Rather than relying on individual “query” documents—e.g., “Find me all (partial) reprints of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s ‘The Celestial Railroad’” —we want to effectively compare each newspaper issue to all other issues—an “all-to-all” comparison—to find both extended quotations and partially or fully reprinted texts.

To identify recurring texts, we rely on high-precision features such as matching word n-grams and on pruning pairs of issues with small n-gram overlap. N-grams are continuous sequences of “n” number words; a 5-gram, then, is a sequence of 5 words. Our methods for pruning the search space, while they might lead us to miss some reprints, are necessary due to the large number of potential all-to-all comparisons. If done exhaustively, for example, our analyses on 52,177 pre-1861 newspaper and magazine issues would have required comparing 1,361,193,576 pairs of issues. This means that if, somewhat optimistically, we could align 10 pairs of issues per second, it would take more than four years to examine the whole collection for reprints.

Moreover, the tools for finding clusters of reprinted texts are designed to work with the error-full output of optical character recognition (OCR) systems and to find reprints embedded within much longer documents such as newspaper issues. The newspapers in the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America collection divide each issue into pages, not logical articles, and the Making of America magazine collection specifies only the page on which each article begins. In contrast, the National Library of Australia’s Trove newspaper collection specifies the zone on each page for each substantial article, although it groups advertisements, obituaries, and other short notices into larger chunks. It is worth noting, however, that many of the shorter reprinted texts we have found, such as jokes or personal anecdotes, are included without any distinguishing titles or separators in such “filler” articles of short extracts. Our task therefore requires somewhat different techniques compared to some previous work on duplicate detection for web documents and plagiarized student papers, or on finding repeated “memes” of only a few words (Leskovec et al., 2009; Suen et al., 2012). A flexible approach to textual boundaries provides further advantages when searching for newspaper reprints: even if we knew the boundaries of articles, we still aim to find—and do find, in many cases—reprints of parts of speeches or individual stanzas of poems or of popular texts embedded, without attribution, in longer articles.

In summary, we aim to detect, without knowing the boundaries of articles, substantial repeated passages of tens to thousands of words embedded within unrelated newspaper issues of tens of thousands of words. Additionally, we seek to find these repeated passages among thousands or millions of distinct newspaper issues and in the presence of significant errors in optical character recognition transcriptions of the page images. In the following subsections, we explain the approach in more detail and comment on some of the design choices in our system for searching OCRed periodicals for clusters of reprinted texts. Our current system compares whole newspaper issues to find matching texts contained within them, but in what follows, we talk more generically of “documents” in order to stress the generality of the approach.

-

Search for Candidate Document Pairs

We begin with a scan for document pairs likely to contain reprinted passages. We use “shingling,” which represents documents by an unordered collection of its n-grams, to provide features for document similarity computations. We balance recall and precision by adjusting the size of the shingles and the proportion of the shingles that are used to calculate document similarity. We build an index of the repeated n-grams and then extract candidate document pairs from this index.-

N-gram Document Representations

The choice of document representation affects the precision and recall, as well as the time and space complexity of a text reuse detection system. In our experiments, we adopt the popular choice of “shingled” n-grams, contiguous subsequences of n words. Very similar passages of sufficient length will share many long n-grams, but longer n-grams are less robust to textual variation and OCR errors. In previous work on detecting short quotes or “memes,” short contiguous n-grams have been proven to be quite effective. Suen et al. (2012), for instance, use 4-grams to identify similar quotes in newspaper articles and blogs. For the newspaper texts, we found word 5-grams achieved an acceptable trade-off between detecting a significant number of pairs of issues with aligned text without retrieving too many pairs of issues with spurious similarity. We illustrate the algorithm with the three document fragments in Figure 2. The first four 5-grams in document #1, for example, are:- her majesty deares to congratulate

- majesty deares to congratulate the

- deares to congratulate the president

- to congratulate the president upon

Figure 2: Three sample OCR text fragments drawn from articles about the completion of the transatlantic telegraph cable.1 her majesty deares to congratulate the president upon the successful completion of this great intern 1 lions work 2 the ueen desires to congratulate the p esident upon the successful completion of the gre it internaliooal work 3 the queen deiirea to congratulate the president upon the euccetwfal completion of thia great inter tatioral work -

Efficient N-gram Indexing

The next step is to build for each n-gram feature an inverted index of the documents where it appears. As in other duplicate detection and text reuse applications, we are only interested in the n-grams shared by two or more documents. The index, therefore, does not need to contain entries for the n-grams that occur only once, which allows us to reduce the size of our index by more than 50%. Returning to the three example documents in Figure 2, an index of the repeated 5-grams would contain the following three entries with the documents in which they appear and the positions in those documents:- to congratulate the president upon: (1,4), (3,4)

- congratulate the president upon the: (1,5), (3,5)

- upon the successful completion of: (1,8), (2,9)

Even though the final index can omit singleton n-grams, the most straightforward approach to counting n-grams requires that we record all the singletons in intermediate storage until we have processed the entire collection. Consider a simple algorithm where we divide the collection into n-gram shingles and then sort the shingles in lexicographical order. A linear scan through the sorted file would easily identify repeated n-grams, but this sorted file would have to contain all the n-grams in order to avoid missing any repeated ones. For instance, if the first and last 5-gram in the file were identical, we would not be able to discard the first 5-gram while any amount of text shorter than the whole collection intervened.

To reduce the intermediate storage requirements, which can be significant for a large corpus, we adopt the space-efficient two-pass algorithm described in Huston et al. (2011). In particular, the variant of the algorithm they name Location-Based Two-Pass works as follows. In a first pass over the collection, each n-gram is mapped to a b-bit numeric value. This hashing operation randomly maps arbitrary strings to a number (hash codes) between 0 and 2b-1. At this stage, we are willing to accept some moderate number of collisions, i.e., different n-grams with the same hash code. The idea is that if b is small enough, we can detect repeated hash codes in much less space than repeated n-grams, which may have words of arbitrary length. If a hash code appears only once, then the n-gram that produced it must necessarily appear only once. After producing this index of hash codes, we then make a second pass over the collection and look up the actual n-grams corresponding to repeated hash codes. If there has been a collision, it is possible that a singleton n-gram mapped to the same code as other n-grams, and we can drop the singletons at this stage. This means that we will not have any false negatives in detecting repeated n-grams and will pay a time cost for false positives as a function of b. If b is too small, for instance, most n-grams’ hash codes will collide, and we will not save anything with the first pass; if b is too large, we will have almost no collisions, but the hash codes will be so big that they will take just as much space as the original n-grams. -

Extracting and Filtering Candidate Pairs

Once we have an inverted index of the documents that contain each n-gram, we use it to generate and rank document pairs that are candidates for containing reprinted texts. As shown above, each entry, or posting list, in the index contains a set of pairs (di, pi) that record the document identifier and position in that document of that n-gram. Once we have a posting list of documents containing each n-gram, we output all pairs of documents in each list. We suppress repeated n-grams appearing in different issues of the same newspaper. Such repetitions often occur in editorial boilerplate or advertisements, which, while interesting, are outside the scope of this project. We also suppress n-grams that generate more than some fixed number of pairs (5000 in our experiments). These frequent n-grams are likely to be common fixed phrases. Filtering terms with high document frequency has led to significant speed increases with small loss in accuracy in other document similarity work (Elsayed et al.). We then sort the list of repeated n-grams by document pair, which allows us to assign a score to each pair based on the number of overlapping n-grams and the distinctiveness of those n-grams. For the example documents from Table 1, the resulting list of document pairs, along with their matching 5-grams, would contain:- (1,2): upon the successful completion of

- (1,3): congratulate the president upon, upon the successful completion of

-

-

Local Document Alignment

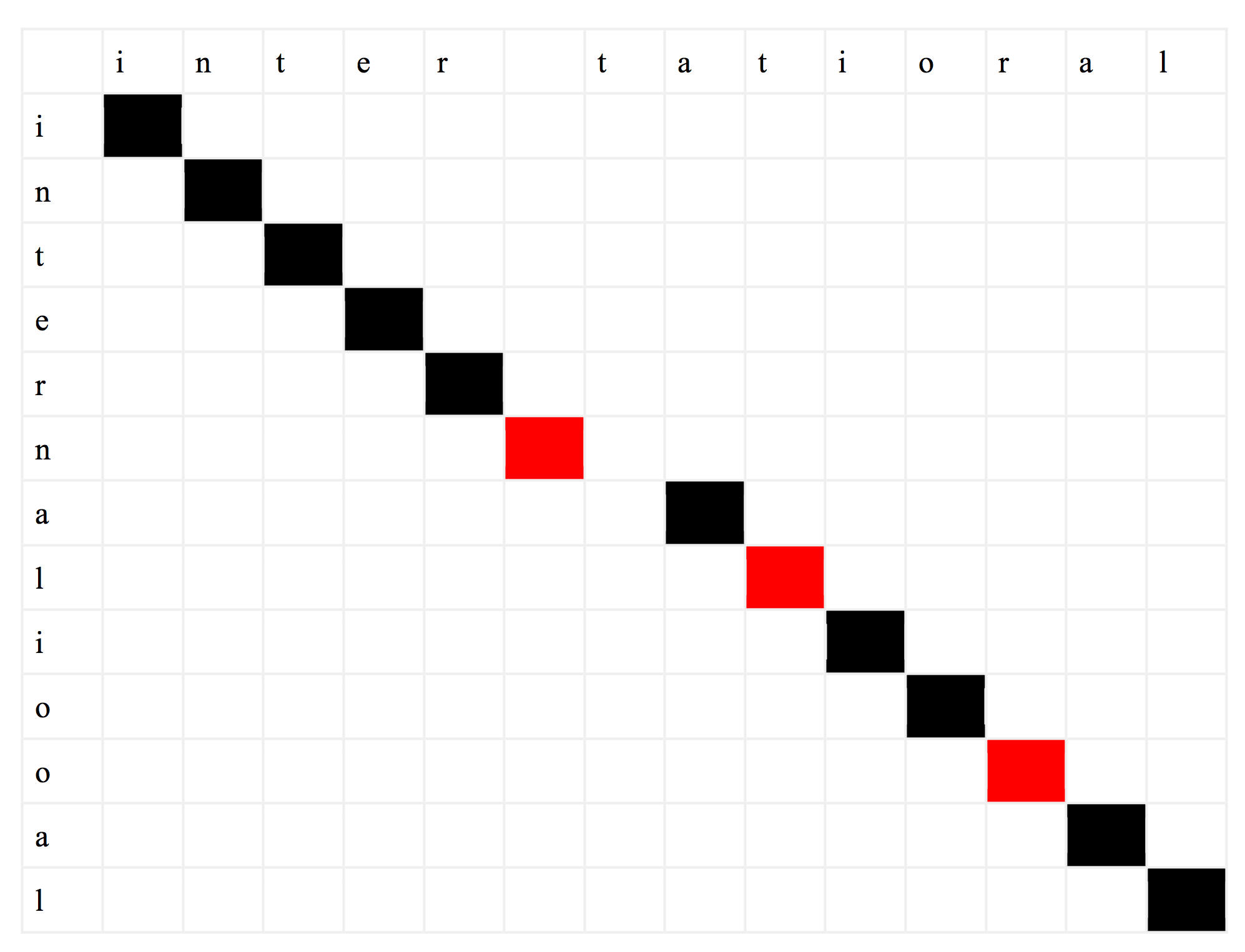

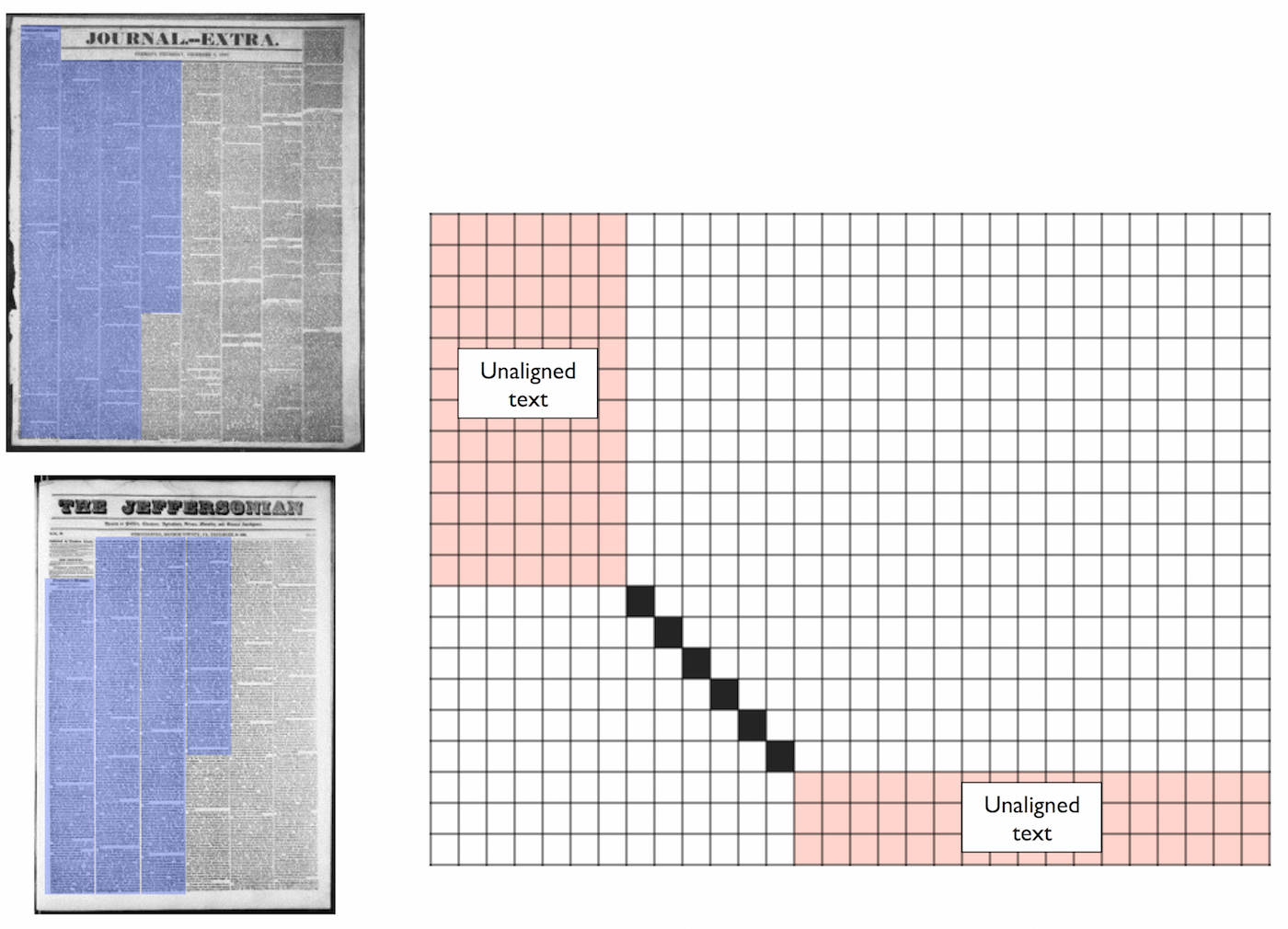

The initial pass returns a large ranked list of candidate document pairs, but it ignores the order of the n-grams as they occur in each document. We therefore employ local alignment techniques to find compact passages within each document in a pair with the highest probability of matching. Due to the high rate of OCR errors and editorial changes during the antebellum period, many n-grams in matching articles will contain slight differences. For example, Figure 3 shows a character-by-character alignment between two mistranscribed words from the texts in Figure 2. A simple Levenshtein edit distance model, which is commonly applied in natural language processing (see, for instance, Gusfield’s textbook for an extensive discussion), aligns these two strings with three character substitutions (in red) and one character insertion. Unlike some partial duplicate detection techniques based on global alignment (Yalniz et al.), we cannot expect all or even most of the articles in two newspaper issues, or the text in two books with a shared quotation, to align. Rather, as in some work on biological subsequence alignment (Gusfield), we look for regions of high overlap embedded within sequences that are otherwise unrelated. Diagrammatically, if we lay the entire content of one text along the horizontal cells of a table and the entire content of the other text along the vertical, we do not necessarily want to find an complete alignment from the upper left to the lower right, as in Figure 3, but a partial alignment surrounded by unrelated material, as in Figure 4. To find such a local alignment, we employ the Smith-Waterman dynamic programming algorithm. The time complexity is the same as the Levenshtein edit distance algorithm and is proportional to the product of the lengths of the two texts to be aligned. We achieve significant speed improvements by forcing the alignment to contain the 5-gram matches already detected in the previous step. For a detailed description, see the appendix to Wilkerson et al. (2015). This use of model-based alignment distinguishes this approach for other work, for detecting shorter quotations, that starts with areas of n-gram overlap (Kolak and Schilit, 2008; Horton et al., 2010) and then expands them by a fixed number of words. Figure 3: The word ‘international’ is mistranscribed in document #2 and #3 in Figure 3 above, but the texts still match at many points. This figure shows the best such alignment according to a simple model of character edits, with matches in black and mismatches in red. Note also the insertion of the extra character ‘t’ about halfway through the alignment.

Figure 3: The word ‘international’ is mistranscribed in document #2 and #3 in Figure 3 above, but the texts still match at many points. This figure shows the best such alignment according to a simple model of character edits, with matches in black and mismatches in red. Note also the insertion of the extra character ‘t’ about halfway through the alignment.

Figure 4: The aligned portion of two newspapers, highlighted in blue, will typically be surrounded by unrelated content. We thus seek to identify some pair of passages, with unknown boundaries, that match well, as indicated in black in the diagram, without penalizing the inability to find good matches in the red regions.

Figure 4: The aligned portion of two newspapers, highlighted in blue, will typically be surrounded by unrelated content. We thus seek to identify some pair of passages, with unknown boundaries, that match well, as indicated in black in the diagram, without penalizing the inability to find good matches in the red regions. -

Passage Clustering

We now have a set of aligned passage pairs. We sort passage pairs in descending order by length and cluster the passages into larger groups of reprinted texts. If two passages in the same document overlap by 50%, they are taken to be “the same” for purposes of clustering; otherwise, they are treated as different. Given this placement of passages into equivalence classes, we can view this step as detecting connected components in the graph of aligned passages. This algorithm is also called “single-link” clustering, since it only requires a single alignment between passages to join the clusters containing them into a larger group. Figure 5 shows the beginnings of three sample texts, out of 49, in the current clustering of texts on the completion of the transatlantic cable. All three texts begin with a different word, besides containing many other points of disagreement due to OCR errors and changes by each newspaper. The pairwise alignment in the previous step would not have matched ‘The’ with ‘Queen’ or with ‘Victoria’. There was at least one other text with each variant in the corpus, however, and that allowed the cluster to identify the correct boundary.

Figure 5: The beginning of three sample texts, out of 49, of the cluster of reprinted texts on the completion of the transatlantic cable.1858-08-17 Cleveland Morning Leader QUEEN'S MESSAGE!To the Hon. the Psesidkxt or the United States : Her Majesty dea'res to congratulate the President upon the successful completion of this great intern 1 Lions! work in which the 1858-08-19 Belmont Chronicle THE QUEEN'S MESSAGE.VALENTIA, via. TRINITY BAY. Aug. 16.a To Honorable the President of the United States: Her Majesty desires to congratulate the President upon tlie successful completion of this sreat international 1858-08-19 Marshall County Republican Victoria's Message. To the IIo7ivralh;the PreAJi'nt(ihe Um: l'cik States; ' V ' , Her Majesty desires to congratulate the President upon the successful completion of this great international work, in which

III. A Description of Our Newspaper Groupings

For the purposes of mapping and network analyses, we have built a database of publication “families” that gather different iterations of newspaper (e.g., the Nashville Union and the Nashville Union and American), as well as different editions (daily, weekly) of a single publication that are catalogued separately in the Library of Congress’s metadata. This prevents, for instance, two versions of what is essentially the same publication being shown as closely related in a network graph, as well as greatly decreasing the number of elements in these visualizations, thus making them easier to read and interpret. We provide details about this clustering, as well as directions for finding out publications data, in the following. Also, our publications data works in relationship to our data about textual clusters, so that in a given cluster in the database the period-appropriate names of newspapers will appear, rather than the overarching family name.

The publications tab of our in-progress web database brings together details about the publications in our data. To browse this data, one can load the alpha database at http://viraltexts.northeastern.edu. The “clusters” data reflects more recent experiments with the full nineteenth-century holdings in the Chronicling America and Making of America archives. The clusters side of the database is still in active development, and not all features currently work. Our publications data is available under the “Publications” tab. Each field in the record for each publication provides metadata, some of which comes from the Library of Congress website, and some of which represents original research by Viral Texts Ph.D. student Abby Mullen.

-

Interpreting Dates Related to Publication Details

The database’s structure requires that for each date entry we provide a month, day, and year. In many cases, we cannot assign dates with this kind of precision. The best way to recognize and interpret fuzzy dates in the current database is to assume that a date of January 1 in any given year actually indicates sometime within that year, and not the specific date of January 1. The same is generally true of an ending date of December 31. -

Interpreting Publication Records

Each record represents one “family” of newspapers. A family comprises newspapers connected in several ways.-

Name Changes

Newspapers often change names while remaining essentially the same paper. When these name changes occur, Chronicling America creates a separate ID number for the new name, as though the paper was a separate entity from its predecessor. Though this granularity is useful for cataloging, it is less useful for identifying reprinted texts across newspapers or for visualizing connections among newspapers. Thus, we have grouped papers together when they make up a continuous progression. There are a few instances in which such continuity is broken. In most cases, when a merger between two papers occurs, we list the new, merged, paper as a separate entity from either of the two papers that constituted it. We have done this because the merged paper often brings new editors and new perspectives. There is, however, a fine line between a merger and a takeover. We have used our best judgment to determine the difference between those two types of combination. More often than not, the merger between two papers results in a paper not extant in our data. A name change also merits a new listing when the name change accompanied a major ideological or political shift (and often new management). In these cases, the change is usually indicative that the first paper went out of business and sold its location and presses (and sometimes subscriber lists) to a new paper. Again here there is latitude for historical judgment. -

Multiple Editions

Many of our publications, particularly the newspapers, published multiple editions over the course of their existence. Since the editors often printed the same texts in multiple editions (say, both the daily and weekly editions), we have chosen to put all editions of the same paper in the same family, to avoid creating large clusters where one edition is merely reprinting another edition of the same paper. We are operating under the assumption that different editions of the same paper reproduce such similar texts that they would not produce fruitful cluster results.

-

IV. Future Work

Future iterations of the Viral Texts Project will aim to address some of the limitations of corpora and method outlined above. While a complete study of nineteenth-century periodicals will always be out of reach, we can expand our corpus dramatically by including additional historical archives in our analysis. As indicated by their limited presence in the data we are releasing with this article, we have also incorporated Cornell University’s Making of America (MoA) archive of nineteenth-century magazines into our study. Early tests with the MoA data have been encouraging, though these collections, too, are much wider after 1861 than before. Certain magazines, such as Scientific American, include many of the most widely reprinted clusters from our current data, and new clusters are emerging among the magazines and between the magazines and newspapers. As the continually-updating clusters in our online database at http://viraltexts.northeastern.edu indicate, we have also expanded our inquiries to include newspapers through the nineteenth century, which has resulted in significantly more clusters (1,767,549 as of February 2015) and much larger clusters, with up to 150 reprints of some texts from 475 newspaper families. Our experiments with the full nineteenth-century corpora from Chronicling America and Making of America are more speculative than those we report on in this article, however, and will be fully addressed in future publications.

We are working to expand our analysis in several other ways as well. First, we are exploring paths to gain access to commercial archive data. At Northeastern University we can access other databases through our library, such as ProQuest’s American Periodicals Series Online and Readex’s America’s Historical Newspapers, but those subscriptions permit only basic search access to the data. The raw text data that underlies those search capabilities, and which would be necessary for the kinds of computational text analysis described here, are typically not made available, at least by default, even to subscribing libraries. We are currently negotiating with several commercial database providers for research-level access to their text data, which would enable us to extend the results of our research significantly.

In order to gauge the representativeness of our findings, we have tested a selection of our most frequently reprinted texts against these other databases using keyword searches. Those tests indicate that our computationally uncovered reprint clusters do seem indicative of wider popularity in antebellum periodicals. For example, we automatically identified 43 reprintings in Chronicling America of a paragraph-long reflection on immortality by George D. Prentice that was variously titled “The Broken Heart,” “A Beautiful Extract,” “A Beautiful Reflection,” “After Life,” “An Eloquent Passage,” and “Man’s Immortality” (and often attributed in reprintings to Bulwer). Using manual searches, we found 20 (full or partial) reprintings of this same piece in Readex’s America’s Historical Newspapers, 66 in ProQuest’s American Periodicals Series Online, and 42 in Google Books’ nineteenth-century holdings. Some of these duplicate our findings in Chronicling America, but most are new witnesses. This same pattern holds when testing other automatically identified text clusters from our project against other digital archives. Despite the limitations of our corpus, then, our findings appear to be strongly indicative of wider reprinting across nineteenth-century periodicals.

Despite the important findings of our early work with the Chronicling America and Making of America archives, we know also that the nationalistic view of antebellum American print culture our project has thus far uncovered is itself artificial—a product as much of the corpora we have used for text mining as of the realities of nineteenth-century print practices. We know from previous scholarship and some evidence in our findings that American newspapers frequently reprinted from newspapers, magazines, and books produced overseas. To cite only one example, one of the most widely reprinted poems we have uncovered is “The Inquiry” by Scottish poet Charles MacKay, which appeared in hundreds of U.S. newspapers over decades. To this end, we are exploring partnerships with a range of international researchers that would allow us to incorporate transatlantic and even trans-language comparisons into our study, giving us a wider picture of how nineteenth-century Americans exchanged texts internationally.

Finally, we are experimenting with new iterations of our discovery algorithm that attempt to capture shorter reused text sequences. Experiments along this line thus far have introduced significant noise to the study, capturing more mastheads, advertisements, and other repeated texts outside the scope of this study, along with the desired lyric poems and short prose pieces we hope to better identify. Each iteration captures more clusters, however, and we look forward to honing our approach continuously to expand our findings. One of the primary reasons we want to bring this project to wider attention is so that experts across the fields of Viral Texts’ purview can help us discern what kinds of texts we are missing so that we can improve the tool’s ability to find such texts. The Viral Texts database will never be a finished and polished archive, but instead an evolving and experimental space for exploring text reuse across an expanding set of corpora.

Works Cited

- Elsayed, T., J. Lin, and D. W. Oard, "Pairwise Document Similarity in Large Collections with MapReduce, in ACL Short Papers, 2008.

- Gusfield, Dan, Algorithms on Strings, Trees, and Sequences, Cambridge (Cambridge UP), 1997.

- Huston, S., Moffat, A., and Croft, W.B., Efficient Indexing of Repeated N-grams," in Proceedings of Web Search and Data Mining (2011), 127–136.

- Smith, David, Ryan Cordell, and Elizabeth Maddock Dillon, “Infectious Texts: Modeling Text Reuse in Nineteenth-Century Newspapers," Proceedings of the Workshop on Big Humanities (IEEE Computer Society Press), 2013 (accessed 9 April 2014).

- Smith, T. F., and M.S. Waterman, “Identification of Common Molecular Subsequences,” in Journal of Molecular Biology 147.1 (1981): 195–197.

- C. Suen, S. Huang, C. Eksombatchai, R. Sosič, and J. Leskovec, "NIFTY: A system for large scale information flow tracking and clustering," in the Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW), 2013.

- Wilkerson, J., Smith, D. A., Stramp, N., “Tracing the flow of policy ideas on legislatures: A text reuse approach.” American Journal of Political Science, 2015 (accepted).

- Yalniz, I.Z., E. F. Can, and R. Manmatha, "Partial Duplicate Detection for Large Book Collections, in the Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM), 2011.

Notes

[1]This graph was created in R using the ggplot2 package. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria, 2013. http://www.R-project.org; Hadley Wickham, ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York: Springer, 2009.

[2]For details, see Chronicling America’s “About” page.